.jpg)

Breaking Barriers: Understanding Partial Hospitalization Programs for Recovery

May 23, 2025

Written and reviewed by the leadership team at Pathfinder Recovery, including licensed medical and clinical professionals with over 30 years of experience in addiction and mental health care.

Understanding why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth begins with its unique pharmacological characteristics. Methadone stands apart from other medications for opioid dependency due to its complex properties that require heightened clinical oversight. Unlike buprenorphine or naltrexone, methadone is a full opioid agonist with a long and variable half-life ranging from 8 to 59 hours.

This variability means the pharmaceutical accumulates in the body over time, making it difficult to predict how each person will metabolize the drug—a critical consideration when in-person monitoring isn't possible. The overdose risk associated with methadone is particularly concerning when initiating therapy. Respiratory depression can occur when doses are increased too quickly or when methadone interacts with other central nervous system depressants like benzodiazepines, alcohol, or certain antidepressants.

These interactions can be life-threatening, which is why methadone initiation requires careful titration and frequent clinical assessment to find the optimal therapeutic dose for each individual. Programs committed to responsible telemedicine must carefully evaluate which pharmaceuticals can be safely prescribed and monitored via remote consultation platforms.

Methadone’s status as a full opioid agonist means it activates opioid receptors across the brain and body with no built-in safety ceiling. This sets it apart from partial agonists like buprenorphine, which have a cap on their effect and thus a lower overdose risk. Because increasing methadone doses continue to amplify respiratory and sedative effects, the margin for error is much narrower.

This is a core reason why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth: unsupervised dose changes or missed warning signs can quickly turn dangerous, especially in early treatment phases4. For clinicians and individuals comparing opioid use disorder medications, this unique pharmacology demands in-person care models and frequent monitoring, not remote prescription.

| Feature | Methadone | Buprenorphine |

|---|---|---|

| Opioid Type | Full Agonist (No ceiling) | Partial Agonist (Ceiling effect) |

| Overdose Risk | Higher (Respiratory depression) | Lower (Due to ceiling effect) |

| Telehealth Eligible? | No (In-person OTP only) | Yes (VT, MA, CT, NH) |

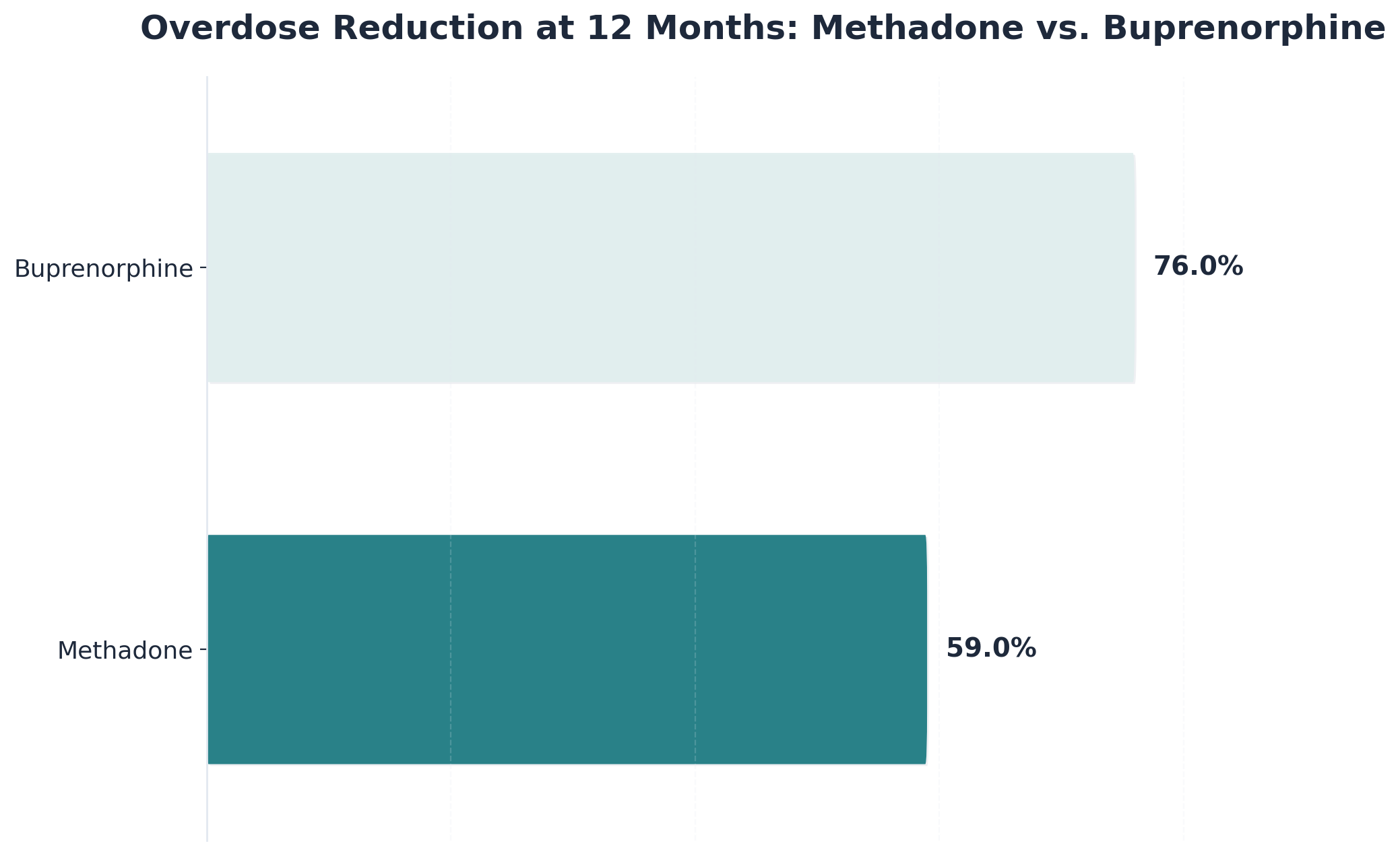

When comparing methadone and buprenorphine, a key distinction is that methadone is a full opioid agonist, while buprenorphine is a partial agonist with a ceiling effect. This means buprenorphine's effects level off at moderate doses, greatly reducing the risk of respiratory depression and fatal overdose—making it much safer for remote prescribing.

In contrast, methadone’s effects continue to rise with each dose, which is why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth and requires in-person oversight for every adjustment4. Studies reveal that both medications are effective, but buprenorphine’s safety margin contributes to its eligibility for telemedicine prescribing10.

Methadone’s half-life—the time it takes for half of the medication to leave the body—varies dramatically between individuals and can range from 8 to 59 hours. This means the drug can accumulate in tissues, even when daily doses remain the same, leading to delayed toxicity or accidental overdose days after starting or increasing a dose.

Because these tissue buildup risks are so hard to predict remotely, clinicians need in-person monitoring to catch early warning signs. This is a central reason why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth; reliable, safe dosing depends on close observation and frequent adjustments based on real-time symptoms4.

Methadone is well known for its potential to cause QT interval prolongation—a change in the heart’s electrical cycle that can lead to dangerous arrhythmias. Studies report that up to 16% of individuals on methadone maintenance therapy experience QTc intervals exceeding 500 ms, a level associated with life-threatening events6.

Because detecting and managing these cardiac effects require electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring and periodic lab work, remote-only care is not considered safe. This is a key reason why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth and instead requires in-person medical supervision.

Methadone’s potential to trigger dangerous heart arrhythmias is not limited by dose—life-threatening QT interval prolongation can develop even at moderate levels, such as 29 mg/day. This means that the risk of cardiac complications spans across dose ranges and can affect individuals unpredictably.

Because these abnormal heart rhythms can arise with little warning, routine in-person ECG and electrolyte checks are considered essential for safe care. This evidence directly supports why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth and why in-person monitoring remains a critical safeguard.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring is a cornerstone of safe methadone therapy. Detecting these changes requires specialized equipment and trained clinicians, which telehealth simply cannot provide. This is a major reason why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth; subtle but critical ECG changes may be missed without in-person assessment.

Studies show that significant QT prolongation underscores the necessity for routine, in-person heart monitoring throughout treatment6. For individuals considering remote care, this method is not suitable when cardiac safety depends on precise, real-time ECG evaluation.

These pharmacological complexities have shaped methadone's unique regulatory landscape. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) established the current framework in 2001 through federal regulations codified in 42 CFR Part 8.

Unlike buprenorphine or naltrexone, which clinicians can prescribe through standard medical channels, methadone for opioid dependency requires dispensing exclusively through federally certified Opioid Treatment Programs (OTPs). This regulatory structure mandates specific operational requirements that distinguish methadone treatment from other addiction medications.

"Certified OTPs must meet stringent federal standards that address the medication's safety profile, including observed dosing protocols and comprehensive support services."

The regulatory framework requires observed dosing protocols during treatment initiation and stabilization phases. Patients typically receive their medication daily at certified facilities under direct staff supervision, with take-home privileges granted only after demonstrating stability according to federal criteria. These criteria consider treatment duration, absence of recent substance use, regular counseling participation, and responsible handling of previous take-home doses.

To understand why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth, it helps to look at the federal requirements for dispensing. Only clinics with official OTP certification are authorized to provide methadone for opioid use disorder. These programs must meet exacting standards for patient monitoring, medication storage, and record-keeping.

Industry leaders find that this in-person framework helps minimize diversion and supports patient safety, especially given methadone’s overdose risks7. For individuals or organizations seeking remote care, this path is not an option: federal law restricts methadone to OTPs with on-site dispensing, regardless of patient preference or geography.

The 2025 DEA telehealth rules make it clear why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth: the regulations permanently exclude methadone from remote prescribing outside of federally certified OTPs. While the rules expand access for buprenorphine—allowing initiation by phone or video for up to six months—methadone remains strictly limited to in-person evaluation and on-site dispensing.

This approach works best when safety and diversion prevention are top priorities, given methadone’s higher risk profile compared to other medications for opioid use disorder1. For individuals and providers exploring virtual care, these federal restrictions mean that telehealth is not an option for methadone.

Daily supervised dosing is a core reason why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth. Federal regulations mandate that new patients receive methadone on-site at OTPs under direct observation, with take-home privileges granted only after strict criteria are met. These rules help prevent diversion and accidental overdose—challenges amplified by methadone’s lack of a safety ceiling.

Even after recent flexibilities, take-home doses are capped for all but the most stable individuals, and unsupervised use is tightly controlled by OTP staff7. This approach suits situations where patient safety and medication security outweigh convenience.

Striking a balance between preventing methadone diversion and expanding access to treatment is a longstanding challenge. Historically, regulators have prioritized diversion control, resulting in daily clinic visits and tight take-home restrictions for methadone patients9. These efforts address why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth—remote prescribing could make it easier for medication to be misused or sold.

However, this safety-first approach can also create real barriers for people in rural areas or with limited OTP access, fueling ongoing debates about health equity. This method works when the goal is to prevent nonmedical use at all costs, but it can unintentionally limit treatment reach for those who might benefit most from expanded telehealth OUD services1.

Since the 1970s, federal policy has focused on preventing methadone diversion. Early regulations mandated daily, in-person dosing at OTPs, aiming to prevent misuse and accidental overdose due to methadone’s potent, full agonist action9. Despite growing calls for expanded access, these controls have persisted through decades of policy, reinforced by methadone’s unique risks and unpredictable metabolism.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, federal agencies temporarily relaxed some methadone dispensing guidelines—most notably by allowing longer take-home supplies for stable individuals. However, these reforms did not authorize remote prescribing, nor did they change the requirement for on-site, in-person dispensing.

This is a key aspect of why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth: even as telemedicine expanded access for other medications, methadone remained strictly regulated due to its risk of diversion, overdose, and the need for close supervision8. Telehealth models for methadone continue to be excluded, with virtual care limited to specific evaluation scenarios within OTPs only.

The initial weeks of medication-assisted treatment represent a critical stabilization period that requires structured clinical oversight to ensure both safety and treatment success. Understanding what this monitoring entails helps patients prepare for the commitment required during early treatment phases.

During the first week of methadone treatment, patients typically attend the clinic daily. These visits serve multiple purposes: dispensing the medication under observation, assessing vital signs including heart rate and blood pressure, and conducting brief clinical evaluations to monitor for signs of oversedation or inadequate dosing.

CLINICAL ALERT: INDUCTION PHASE -------------------------------- 1. Monitor Pupil Size 2. Check Respiratory Rate 3. Assess Level of Alertness 4. Review Patient-Reported Symptoms The titration process follows a careful timeline. Most protocols begin with conservative dosing, gradually increasing the amount over 5-10 days based on individual response. Patients often describe this period as requiring patience, as therapeutic levels build slowly due to methadone's extended half-life. Clinical staff track accumulation patterns, watching for the point where medication levels stabilize—typically occurring between days 3-5.

During the induction phase of methadone treatment, close clinical monitoring is essential because the risk of respiratory depression—slow or shallow breathing that can lead to fatal overdose—is highest in the first week. Research highlights that methadone’s full opioid agonist effect, unpredictable half-life, and slow tissue buildup can cause delayed toxicity, even if the daily dose seems unchanged4.

This explains why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth: subtle signs of respiratory suppression or overdose often require immediate, in-person response by trained staff, which remote care cannot replicate. For individuals with polysubstance use or unknown tolerance, in-person induction offers the necessary safety net.

During the first week of methadone treatment, the risk of overdose is highest due to methadone’s narrow therapeutic window and slow, unpredictable buildup in body tissues. Even when the daily dose stays the same, individuals may experience delayed respiratory depression or severe sedation, which often develops too slowly for self-detection.

This is at the heart of why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth: without daily, in-person monitoring, subtle warning signs are easily missed, and timely intervention is not possible. Studies highlight that such risks are magnified for those new to methadone or without established opioid tolerance, making remote-only induction unsafe4.

Drug interactions and polysubstance use are major reasons why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth. Methadone’s effects can be dangerously amplified by common substances such as benzodiazepines, alcohol, or even certain antidepressants and antipsychotics. These combinations raise the risk of life-threatening respiratory depression and sedation.

Studies emphasize that the unpredictable mix of methadone with other drugs makes remote assessment for overdose warning signs unreliable; only in-person observation allows for rapid detection and intervention if symptoms appear4. This approach is necessary for individuals with co-occurring substance use.

Frequent toxicology testing and precise dose adjustments are essential during early methadone treatment, which illustrates why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth. Regular urine drug screens help clinicians detect undisclosed substance use or interactions that could increase overdose risk, while in-person observation allows for real-time response to evolving symptoms.

Telemedicine platforms simply cannot provide the instant lab testing, direct supervision, or immediate dose modifications required to keep methadone induction safe4. This method works when rapid detection and intervention are needed—especially in the first weeks, when individual metabolism and external factors can shift quickly.

Real-time symptom assessment is a non-negotiable part of early methadone treatment. Because methadone’s effects can change rapidly with subtle signs of toxicity—such as drowsiness, confusion, or slowed breathing—only in-person visits allow for instant recognition and response by medical staff.

Research underscores that telemedicine simply cannot match the ability of on-site providers to detect early warning signs or act on lab results and physical cues before making dose changes4. This solution fits individuals who require close, real-time supervision during induction.

Video-based evaluations might seem convenient, but they simply cannot replace the safety and accuracy of in-person methadone assessments. While video visits can help gather patient history or observe visible symptoms, they miss critical elements like subtle physical signs of toxicity, changes in breathing, or immediate access to lab results.

This limitation is central to why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth: even high-quality video cannot detect slight changes in pupil size, muscle tone, or early respiratory depression that trained clinicians routinely catch during face-to-face visits. Studies and federal guidance consistently point out that safe methadone induction requires hands-on monitoring4.

Before pursuing telehealth medication-assisted treatment, individuals should carefully evaluate whether this care model aligns with their specific clinical needs and personal circumstances. The following framework can help determine if virtual MAT is an appropriate choice.

Programs prioritizing research-supported standards carefully assess each person's clinical profile before recommending telehealth MAT. This individualized approach ensures that virtual care serves as a safe, effective option rather than a one-size-fits-all solution.

When selecting medication-assisted treatment, understanding why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth is crucial. Methadone’s unique safety risks and federal regulations mean it can only be dispensed in person at certified opioid treatment programs. By contrast, buprenorphine and naltrexone offer much more flexibility, with research showing telehealth MAT for these medications can achieve similar retention rates and expand access for people in Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire2.

This approach works best when individuals value convenience, need to fit care into a busy schedule, or live far from treatment centers. On the other hand, if your clinical needs or safety concerns point toward methadone, in-person OTP care is non-negotiable due to the medication’s full agonist profile and monitoring requirements.

Buprenorphine and naltrexone offer distinct advantages for those seeking medication-assisted treatment (MAT) through telehealth. Buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist, can be prescribed remotely by clinicians with the appropriate DEA waiver, making it a strong fit for individuals needing flexible, at-home care. Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, is also telehealth-eligible, though starting treatment requires confirmation that the individual is free from opioids to avoid withdrawal.

Industry findings confirm that telemedicine MAT for buprenorphine and naltrexone achieves similar treatment retention rates as in-person care, helping bridge access gaps in Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire2. This method works well for people juggling busy schedules or living far from treatment centers.

Choosing in-person opioid treatment program (OTP) care is essential when methadone is medically indicated or when safety risks make remote management inappropriate. This scenario is common for individuals with complex health profiles, co-occurring medication use, or those starting opioid use disorder treatment for the first time.

The main reason why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth is that federal regulations and clinical best practices require hands-on supervision, daily dosing, and real-time symptom checks—all of which can only be delivered at certified OTPs7. Research confirms that these protocols protect individuals from overdose and dangerous drug interactions, especially during induction or dose changes4.

For those in Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, or New Hampshire, this timeline helps clarify how telehealth MAT can fit into a busy life, while also highlighting why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth. Studies show that remote MAT programs can maintain strong engagement for eligible medications, but in-person supervision remains non-negotiable for methadone due to federal and clinical safety standards2.

For professionals in Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, or New Hampshire seeking discreet substance use disorder treatment, telehealth MAT can be a practical solution—except when it comes to methadone. The primary reason why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth is twofold: federal regulations only allow dispensing through in-person, federally certified OTPs, and methadone’s safety profile demands on-site dosing supervision and frequent monitoring7.

Research shows these options provide flexibility and privacy without compromising safety, making them suitable for professionals balancing demanding schedules2. If discreet, virtual care is your goal, prioritize telehealth-eligible medications and consult with providers to confirm your best fit.

Families in Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, or New Hampshire exploring virtual treatment often hope to support their loved one’s recovery with flexible, home-based care. Telehealth MAT is a strong fit for families whose member can be safely treated with buprenorphine or naltrexone—these medications meet telehealth MAT eligibility standards and allow for remote appointments, which can ease practical burdens and reduce stigma.

However, understanding why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth is vital: federal law and the medication’s safety profile require methadone to be dispensed only through in-person, federally certified OTPs, with on-site supervision and regular monitoring7. Research shows that remote MAT keeps families engaged for eligible medications, but any need for methadone means in-person care is the only safe and legal route2.

Many people exploring medication-assisted recovery via remote platforms have practical questions about how these programs work in real-world situations.

Pathfinder cannot initiate methadone treatment through its virtual program. This limitation exists because federal regulations require methadone for opioid use disorder to be dispensed only at certified opioid treatment programs (OTPs) with daily, in-person supervision—not through telehealth or remote prescription. The key reason why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth is its safety profile: the medication’s unpredictable metabolism, overdose risk, and the need for frequent monitoring mean virtual-only care is not permitted under current law7. While Pathfinder offers flexible, virtual support for other MAT options like buprenorphine and naltrexone, anyone who needs methadone must receive care at a certified OTP with on-site dosing and supervision.

Virtual medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is designed for flexibility, enabling most individuals in Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire to schedule appointments outside of traditional business hours. Telehealth MAT platforms for buprenorphine and naltrexone typically offer evening and weekend sessions, as well as secure messaging for quick check-ins—making it easier to integrate treatment into a busy work schedule. This approach fits professionals and shift workers who need to balance recovery with job responsibilities. However, why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth directly impacts scheduling: methadone requires daily, in-person visits to a federally certified opioid treatment program (OTP) for supervised dosing, which can be difficult for those with demanding jobs7.

At this time, there are no concrete plans to permit methadone prescribing via telehealth for opioid use disorder outside of federally certified opioid treatment programs (OTPs). Recent DEA and HHS rule changes have allowed some telehealth expansion for buprenorphine but continue to exclude methadone from remote initiation and home-based dispensing. The 2025 DEA telemedicine rules specifically reinforce why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth, maintaining strict in-person requirements due to the medication’s full agonist opioid risk and need for close monitoring1.

If your adult child is hesitant about attending in-person programs, you can still play a supportive role by exploring telehealth medication-assisted treatment (MAT) options. Many individuals prefer the privacy and flexibility of remote care, which makes buprenorphine and naltrexone strong alternatives for those resistant to on-site visits. The key reason why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth is that federal regulations require in-person dosing at certified opioid treatment programs (OTPs), so if methadone is clinically necessary, in-person attendance can’t be avoided7. However, for eligible medications, you can help your child schedule virtual appointments and connect with providers serving Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, or New Hampshire.

Pathfinder uses a multi-layered safety approach for virtual medication management, focusing only on telehealth-eligible medications such as buprenorphine and naltrexone. Every individual receives a structured intake assessment, ongoing symptom monitoring via secure video or messaging, and regular toxicology screens coordinated with local labs. These protocols align with federal and clinical guidelines for telehealth MAT eligibility, ensuring that any warning signs or adverse reactions are caught early. The reason why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth—namely, the need for daily in-person supervision, unpredictable side effects, and federal OTP requirements—means all virtual safety measures are designed for medications with proven remote monitoring safety2, 7.

Yes, if you live in a rural area with limited access to opioid treatment programs (OTPs), you can still receive virtual medication-assisted treatment (MAT)—but only for telehealth-eligible medications like buprenorphine and naltrexone. These medications can be prescribed and monitored remotely, allowing individuals in Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire to access care without frequent travel. However, why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth is rooted in federal law and OTP requirements for methadone: methadone must be dispensed in person at a federally certified OTP due to its safety profile, risk of overdose, and need for close supervision7.

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) options available via telehealth include buprenorphine and naltrexone—both approved for virtual prescribing in Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire. Buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist, can be initiated and managed remotely by a licensed provider with a DEA waiver, making it a strong fit for those who value flexibility and need to access care from home. Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, is also telehealth-eligible, though an in-person lab test is required before starting to ensure the individual is opioid-free. These options are possible because their safety profiles allow for effective monitoring through telehealth MAT platforms, unlike methadone, which is not prescribed via telehealth due to federal restrictions1, 2.

Choosing between buprenorphine and methadone for opioid use disorder depends on your medical needs, safety profile, and access preferences. Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist with a ceiling effect, making it safer for remote prescribing and available via telehealth for eligible individuals in Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire. Methadone, in contrast, is a full agonist, has no safety ceiling, and carries a higher risk of overdose and cardiac side effects—requiring daily, in-person dosing at federally certified opioid treatment programs (OTPs)4, 7. This is a core reason why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth.

Yes, it is possible to transition from methadone at an opioid treatment program (OTP) to virtual care with buprenorphine—but this process requires careful planning and medical supervision. Individuals currently stabilized on methadone must first undergo a medically managed taper, reducing their methadone dose to a low threshold before beginning buprenorphine. This is necessary because starting buprenorphine too soon can trigger precipitated withdrawal due to the different ways these medications interact with opioid receptors. Once the transition is safely managed in-person at the OTP, and withdrawal is confirmed, a provider can initiate buprenorphine, which is eligible for telehealth MAT in Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire4, 7.

Methadone is considered more dangerous than other medications for substance use disorder because it is a full opioid agonist with no safety ceiling, meaning higher doses can lead to severe respiratory depression and overdose4. Unlike buprenorphine, which levels off at moderate doses, methadone’s effects increase with each dose, raising the risk of toxicity—especially during dose changes. Its half-life is highly unpredictable, allowing the drug to build up in body tissues and cause delayed, sometimes fatal, side effects even if the daily amount doesn’t change. Methadone also poses a unique risk for heart rhythm problems, such as QT interval prolongation, which can lead to life-threatening arrhythmias in some individuals6.

For most individuals in Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, or New Hampshire, starting medication-assisted treatment (MAT) with buprenorphine or naltrexone via telehealth can happen within a few days to a week, depending on provider availability and insurance verification. The process typically involves a virtual intake appointment, eligibility assessment, and—if naltrexone is chosen—an in-person lab test to confirm opioid-free status. This speed is possible because these medications have safety profiles suitable for remote monitoring and meet telehealth MAT eligibility standards. In contrast, those seeking methadone will find that why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth means all steps must occur in person at a federally certified opioid treatment program (OTP), which may extend the timeline due to clinic scheduling and daily supervision requirements2.

Most major insurance plans—including Medicaid, Medicare, and many private insurers—cover virtual medication-assisted treatment (MAT) services in Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire, particularly for telehealth-eligible medications like buprenorphine and naltrexone. Coverage for virtual MAT has grown in response to federal and state support for expanding access to opioid use disorder care, and research confirms that telehealth programs achieve strong treatment retention across these states2. However, because why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth relates to federal regulations and OTP requirements for methadone, insurance will only cover methadone if it is dispensed in person at a certified opioid treatment program (OTP)—not through fully virtual care.

Yes, you can receive medication-assisted treatment (MAT) through telehealth even if you have co-occurring mental health conditions—provided the medication is one of those eligible for virtual prescribing, such as buprenorphine or naltrexone. Telehealth MAT programs, including Pathfinder’s, are designed to support individuals with both substance use disorder and co-occurring mental health needs, but they do not provide primary mental health treatment. Instead, these services focus on integrated care: addressing both substance use and related mental health symptoms together. This approach is effective for many, as research shows telehealth MAT can maintain strong engagement for people with complex needs in Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire2.

If you’ve experienced a relapse after previous treatment attempts, you’re not alone—and it’s absolutely possible to re-engage with care that fits your needs. Many people in Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire return to treatment after setbacks, often finding that medication-assisted treatment (MAT) with virtual options like buprenorphine or naltrexone can offer a new path forward. These medications are available via telehealth because their safety profiles allow for remote monitoring, which is not the case for methadone. The main reason why methadone is not prescribed via telehealth is tied to federal regulations and its higher risk of overdose and unpredictable side effects—meaning in-person visits at a certified opioid treatment program (OTP) are still required7.

Understanding why methadone requires face-to-face dispensing helps clarify the broader landscape of medication-assisted treatment and the role of remote healthcare in addiction recovery. While methadone's unique pharmacology necessitates in-person dispensing at certified clinics, other evidence-based medications offer equally effective pathways to recovery through different delivery models.

The central insight from exploring virtual MAT options is that successful treatment depends on matching the right medication to the most appropriate delivery method for each individual's circumstances. Buprenorphine and naltrexone have safety profiles that allow for responsible remote prescribing when combined with proper clinical oversight, while methadone's characteristics make it better suited to structured clinic-based care. Neither approach is inherently superior—they serve different needs within the recovery landscape.

Telehealth has fundamentally expanded the role of addiction treatment by removing traditional barriers of geography, transportation, and scheduling that previously prevented many people from accessing care. Virtual platforms enable consistent medical supervision, regular therapeutic support, and medication management without requiring daily clinic visits. This flexibility proves particularly valuable for individuals balancing work responsibilities, family obligations, or living in areas with limited treatment infrastructure.

Patients considering their care options benefit from understanding these distinctions. Asking providers about medication alternatives, delivery methods, insurance coverage, and program structures empowers individuals to make informed decisions aligned with their recovery goals, lifestyle needs, and medical circumstances. The conversation with healthcare professionals should address not just which medication, but which treatment model offers the best foundation for sustainable recovery.

Programs like Pathfinder serve individuals across Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire by providing access to virtual MAT services grounded in evidence-based protocols. As telehealth continues evolving, more people can access the comprehensive support that recovery requires—wherever they're starting their journey. The expanding availability of both traditional and virtual treatment options means that more pathways to recovery exist today than ever before, giving individuals greater agency in choosing the approach that will best support their long-term wellness.

.jpg)

May 23, 2025

November 6, 2025

November 6, 2025